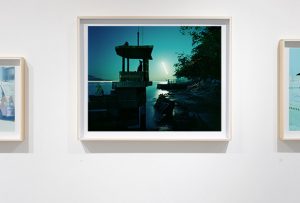

Digital enlargement print (C-type print) from large-format and medium-format colour negative film, Kodak RA-4 Chromogenic paper, variable dimensions. 2016-2020

(click on image for lightbox mode)

2020-1841, a solo exhibition by Thomas LIN

Lumenvism, Hong Kong. Showcasing the EV −3 series.

Thomas Lin, Nov 2020

The work EV −3 connects the early days of colonial Hong Kong with the introduction of photography. Serving as an archive of imaginary future historical photographs, it shows a visual representation of contemporary Hong Kong that relates to its past.

The recent elevating social movements and repressions have pushed Hong Kong into the global spotlight. Though having extraordinary developments in its relatively short history, Hong Kong has witnessed significant transformations, including sovereignty handovers and military occupation. When I examine those people and places of the historic photographs, it feels as though reliving this tortuous past. That inform me of the critical moments people of Hong Kong came up against from time to time.

The 19th century witnessed the expansion of imperialism and technological advancements in Europe. It was during this period that France announced the invention of photography in 1839, coinciding with the outbreak of the First Opium War in China. This conflict resulted in the British acquisition of Hong Kong Island in 1841, marking the beginning of Hong Kong’s colonial history. Soon after, photography reached Hong Kong through the visits of the early Western travellers. This new medium of visual documentation played a crucial role in shaping the narrative of the colony from its earliest days. Despite being a foreign perspective, photography imbues the early impressions of Hong Kong with vividness akin to personal memories. It not only preserved tangible evidence but also captured the emotions of that time as the years went by.

In the early days of photography, due to the long exposure times required even in bright daylight, capturing nocturnal scenes was virtually impossible. When darkness fell and the landscape was merely outlined by moonlight, the only source of illumination was oil or candlelight. It is difficult to imagine that the people of that time could have envisioned Hong Kong, once considered a ‘barren island’ *, evolving into the vibrant modern city it is today.

‘What if the people of 1841 could ever witness our iconic night scenery now?’ This hypothetical scenario sparked my idea of filling the void in the early impressions of Hong Kong by photographing its nocturnal scenery under the eternal glow of moonlight. In photographic terminology, the exposure value required to capture an image solely by the luminance of the full moon is EV −3. However, adopting such a low value for the excessive modern city lights would fiercely overexpose the image, resulting in unpredictable photographic outcomes. To me, this serves as both a metaphor for the city’s uncertain future and a means to express my own emotions through light.

* ‘You have obtained the Cession of Hong Kong, a barren Island with hardly a House upon it.’ Lord Palmerston to Captain Elliot, R.N., 21-4-1841.

Diaspora, Cree, Berlin

Edwin K. LAI, 2020 (中文版在下方)

In the past two years, Hong Kong has experienced tremendous turmoil. Many people worried about the drastic political changes, some wanted to maintain the life they lived before the reunification. This kind of thinking, namely the diaspora mentality, has arisen several times in Hong Kong. A good example is that after the Republican Revolution in 1911, many Qing scholars and officials alike from the Guangzhou area went south, they settled down in Hong Kong but still lived the life in the past.

Diaspora mentality means reminiscence. It lets us learn from, understand and cherish history, and most importantly, re-examine the neglected and forgotten historical course. For Thomas LIN, he chose to focus on the beginning of colonial Hong Kong, a western-style port city on the outskirts of southern China, and the contrast between its dark nights at that time and the metropolitan brilliancy today. He asked: ‘What would it be like if the people of 1841 could ever meet us and witness today’s iconic night views?’

I think the best person to answer this question is Dr. Edward H. CREE (1814-1901), a British naval surgeon who visited Hong Kong several times in the first years for work and leisure. During his stay, he has joined many dinner parties and night trips. Dr. CREE wrote journals, which often accompanied his drawings, which is a fascinating narrative about the early life of Hong Kong. On 25th March (Tuesday), 1845 he wrote:

A picnic had been arranged for the opposite shore of Liemoon (Lei Yue Mun). A lorcha, a large covered boat with a fine cabin, was hired, in case it rained … we started with a fair wind, under black skies, at noon … Of rain and wind we soon had more than enough. We could not land for the surf on the beach, and had to beat our way back to the harbour, in time for dinner on board the Vixen … The weather had cleared, so after dinner we rigged up the quarterdeck, got ROUTH’s piano up, and our three musicians, and were soon kicking our heels up, to the delight of the girls, till near midnight, when we saw all the girls safely home. Next day a dance at McKNIGHT’s where we met the same party, with additions.

At the time, nightlife was under the light of whale oil lamps or otherwise moonlight. In order to simulate this illuminance, LIN’s photographs in this exhibition are taken based on the exposure value of EV −3. As he explained, ‘Adopting such a low value will overexpose the city lights to an unmanageable extent, and the blurry outcomes render the scenes appeared unfamiliar.’ If Dr. CREE could see these photographs, would he feel the same?

What comes to my mind is ‘The Wall’, an early song by the Hong Kong band Tat Ming Pair:

Shuttling in the heart of the street, pedestrians in black pass by, feelings on their faces concealed, wandering slowly in this long road…There is no colour, no light, separates everything.

The song is about post-World War II Berlin, a city that became the new analogy for today’s Hong Kong. Now the new Cold War suddenly focuses on this Asian city, revealing its internal conflicts, and people feel helpless about it. In this 1986 song, lyricist Keith CHAN described East Berlin as sad and desperate. Yet just a few years, the wall that was believed to stand forever was demolished by the German. So while constantly musing on history, I am willing to look on the bright side of the future. Just like vocalist Anthony WONG repeated at the end of the song:

Let there be colours, be light, hoping for in my heart.

Edwin K. LAI, Ph.D. is the Senior Lecturer and Subject Coordinator (Photography) at the Hong Kong Art School, and an internationally recognised scholar of Chinese and Hong Kong photography. He has published more than one hundred essays and articles, and his photographic works have been exhibited in the U.K., Japan and Hong Kong. Starting from 2008, LAI has curated a number of exhibitions about Hong Kong photography and art, including ‘The Earliest Photographs of Hong Kong’ (2010), ‘Post-Straight: Contemporary Hong Kong Photography’ (2012), ‘Twin Peaks: Contemporary Hong Kong Photography’ (2014), and ‘Synchronic’ (2018), to name a few.

遺民、克里醫生、柏林

黎健強 博士 10-2020

這兩年香港社會經歷了很大的動盪,許多人一方面感到典章制度發生了翻天覆地的轉變,另一方面卻希望維持以往的生活方式。這種思想可以稱之為遺民心態,它在香港曾經發生過好幾次:最佳例子是一九一一年中國發生了共和革命之後,不少原本居住在廣州等地的清朝儒生和官民紛紛南下來到香港,繼續過著之前忠君守故的日子。

遺民心態就是懷舊,它最有意義的就是令人學習、認識和珍惜歷史,以至重新審視被忽略忘記了的昔日發展過程。今次 練錦順 選擇了的,是香港這個位於南中國邊陲的西式港口城市的成立初年,以及將當時夜裡的暗黑環境,對照如今霓虹燈光亮透晚上的境況。他問道:「如果一八四一年的香港人能夠與我們見面並見證今天的夜景,該會有何感想?」

回答這個問題的最佳人選,我認為是香港開埠年間多次隨船訪港工作和遊玩的英國海軍軍醫 克里 (Edward H. CREE, 1814-1901)。他在香港期間,常常都有參加晚宴和夜間旅行的活動。克里 醫生有寫日誌的習慣,還每每加上自繪的圖畫,令後人對當年的香港社會產生圖文並茂的印象。例如他記錄的一八四五年三月廿五日(星期二):

「準備了在鯉魚門對岸野餐,為防下雨雇了一艘有蓋和精緻船艙的帆船。……我們在中午烏雲有風時起行,……很快風雨就令我們吃不消了,但又不能在海灘登陸,只好力克風浪回到岸邊,及時趕上在「雌狐」(Vixen)艦甲板上舉行的晚餐。……天氣變得清朗,那麼餐會結束後我們就清理了後甲板,搬出 魯夫 (ROUTH)的鋼琴,三個音樂家隨即大跳特跳,引得女孩子們大樂。直至接近午夜,然後我們才送她們全部安全回家。第二天在 麥禮特 (McKNIGHT)家有舞會,同一班人又來了,而且來的更多。」

在那個年代,晚上都使用鯨魚油燈來照明,甚至月光還是會派上用場的,為了模擬那個照明度,練錦順 在本展覽裡的照片都是根據EV −3的曝光值進行拍攝的。正如他自己所解釋:「採用如此低的曝光值會使得城市的燈光過度曝光至難以控制的程度,其結果令景象顯得模糊而感覺陌生。」如果 克里 醫生能夠觀看到這些照片,他的感受是否也是如此呢?

在我來說,想到的卻是香港樂隊「達明一派」早期作品《圍牆》的歌詞:

「穿梭於街中心穿黑色的行人路過,在面上一絲絲深沉。徘徊在這長長路中慢行。……沒色彩,沒光線,令一切隔開。」

《圍牆》描述的世界當然是第二次世界大戰之後的德國城市柏林,一個這兩年來常常有人比擬當前香港的地方。那時候的冷戰焦點,一下子轉移到來了這個本來內部矛盾不算激烈的小都會,令居民感到十分無辜,嗟歎橫禍無端的飛來。《圍牆》發表於一九八六年,填詞人 陳少琪 筆下的東柏林是憂傷而絕望的;只是過不了幾年,多數人認為永遠不會倒下的圍牆就給德國人民拆毀了。所以我在常常回望歷史的同時,也願意抱著積極的心情迎向未來。正如樂隊的歌者 黃耀明 在歌曲結束時交錯唱著的幾句:

「讓色彩,讓光線,在心裡期待。」

黎健強 博士是香港藝術學院高級講師及攝影學科統籌,也是國際知名的中國及香港攝影學者。 他曾經發表文章超過一百篇,攝影作品在英國、日本及香港展出。2008 年起黎氏策展過多個攝影及藝術展覽,包括:《香港最早期照片 1858-1875》(2010)、《後直:當代香港攝影》 (2012)、《屾:當代香港攝影》(2014)、《 此時這地香港學苑攝影》(2018)。

2019年7月1日

菱田雄介 2020 (scroll down for English version / 中文版在下方)

2019年7月1日、返還から22周年となるこの日、香港の街は激しい熱にうなされていた。セントラル(中環)の大通りを埋め尽くす人の流れに圧倒されながら私は、歴史がまさに動きつつあることを感じた。

強い光を放つ太陽が西に沈む頃に人々の流れは変わり、立法府の付近に滞留するようになった。ゴーグルやマスクで顔を覆い、食品用のラップで手足をぐるぐる巻きにした若者たちが続々と集まってくる。催涙弾がいつ打ち込まれてもおかしくない情勢になろうとしていた。

群衆を見下ろす歩道橋の上には世界中からやってきたカメラマンがずらりと並んでいる。望遠レンズを付けたデジタル一眼レフがひしめき合う中で、なぜか4×5判の大判カメラを三脚に据えた人の姿が目に止まった。一瞬、一瞬を切り取ろうとするカメラマンの横で、シャッターを切ることなく悠然と構えるその人物が、練錦順 だった。

カメラに詳しい人ならわかると思うが、大判カメラはおよそ報道写真には向かない。フィルムは一枚ずつ交換しなければならないし、長い露光時間が必要なので、夜間の撮影だとブレてしまうのだ。不思議に思った僕が話しかけると、この不思議な写真家は香港の歴史を語り始めた。月の光と香港が辿ってきた歴史の話だった。

今、その時に撮影された写真を見ている(EV −3 26)。白く光る画像をよく見ると、画面を斜めに貫く車線に気づく。その傍でうごめく群衆が、流れる水のような軌跡を描く。動くものと動かないもの。遥か昔からこの土地で繰り返されてきた歴史を考えずにはいられない。

練錦順 の〈EV −3〉は、1841年の香港人が2020年の香港に出会ったらどのように見えるのか…という発想から生まれた作品だという。1841年は、イギリスが香港島を占領した年だ。翌年に結ばれた南京条約によって、香港はイギリスに永久割譲されることとなる。

練錦順 が生み出したイメージを見て感じるのは、静謐さと激しさという相反する二つの感覚である。

「EV −3 16」は月明かりに照らされた入江の写真だ。この土地がまだ人間の文明を知らなかった時代を想起させる。月光だけが夜の支配者だった時代。人類の歴史を遡れば、香港は常にこのような姿をしていたのだと思う。しかし、近代史は香港を放ってはおかなかった。英国領として独自の発展を遂げたこの街は、まばゆい光を放つ国際都市へと変貌する。「EV −3 22」に象徴されるこの光景は、人間の飽くなき欲望の結晶だ。

そして今、香港の歴史は大きく揺さぶられている。中判カメラで撮影された若者たちのポートレート。彼らを浮かび上がらせるのは、月の光ではなく、スマートフォンの光である。激しくブレた画面の中で、不安定な未来を生きようともがく若者たちの意思を感じる。

「ゆく川の流れは絶えずして、しかも、もとの水にあらず。淀みに浮かぶうたかたは、かつ消えかつ結びて。久しくとどまりたるためしなし。世の中にある人と、栖とまたかくのごとし。」(〈方丈記〉鴨長明)

12世紀の日本の随筆家、鴨長明 の文章である。私たちが住む国や街も、大きな歴史を漂う水のように絶えず流れ続ける。その流れは決して止まることはない。ただし、その流れを作っていくのはその土地に住む人々である。

香港についてのニュースが溢れる中、〈EV −3〉は、私たちの視線をより高い場所へと運ぶ。香港という特殊な街が辿ってきた歴史と、それを照らし続けた月の光を考える。

冒頭の入り江の写真。もしかするとこれは過去の光景ではなく、未来の光景なのかもしれない。

菱田雄介、1972年東京生まれ。写真家‧映像ディレクター。歴史とその傍らにある生活をテーマに撮影。〈border〉東京都写真美術館「日本の新進作家」選出 (2020)。著書/写真集に〈2011年123月〉(彩流社 2021)、〈border | korea〉(リブロアルテ 2017)、〈2011〉(vnc 2014)、〈アフターマス‧震災後の写真〉(飯沢耕太郎氏との共著 NTT 出版 2011)、〈BESLAN〉(新風舎 2006)、〈ある日、〉(プレイス M/月曜社 2006)。〈border | korea〉にて、第30回「写真の会」賞受賞 (2018)。キヤノン写真新世紀佳作 (2008‧2010)、ニコン三木淳奨励賞 (2006)。作品は東京都写真美術館、Seoul Museum of Art、金浦文化財団が収集しています。

1st July, 2019

HISHIDA Yusuke, 2020

On July 1st, 2019, the 22nd anniversary of the handover, I was overwhelmed by the flow of people filling the Central area in Hong Kong, I felt the heat and sensed the turmoil, history was flipping to another page.

When sunset, the crowd huddled near the Legislative Council of Hong Kong. Youngsters, their faces were covered with goggles and masks, their arms and legs were wrapped around in plastic wraps, gathered one after another. We were about to be in a position where tear gas would be fired at any time.

Cameramen from all over the globe lined the pedestrian bridge overlooking the rally. While professional digital cameras equipped with telephoto lenses were packed with each other, and next to the photographers who didn’t waste any second to catch every scene, I saw Thomas LIN with a large 4×5 camera on his tripod. He just stood still without closing the shutter.

Anybody familiar with cameras knows, large format cameras are not suitable for press photos: films have to be replaced one by one, it takes a long time for exposure and it blurs when shooting at night. When I spoke to Thomas, he began to talk about Hong Kong, though his story was not about democracy or the rally but about the moonlight and the long history of the former British Colony.

Now I’m looking at the photo taken at that rally (EV −3 26). If you look closely at the glowing white image, you will notice the lane that runs diagonally through the picture, crowds wriggle beside the lane draw water-like trajectories. It shows things that move and things that don’t. I can’t help but think about the history of Hong Kong that has been repeated in this place for a long time.

Thomas LIN’s EV −3 was born out of the idea of how Hong Kongers who lived in 1841 would see their city in 2020. In 1841, Hong Kong Island was occupied by the British. Hong Kong was permanently ceded to Britain by the Treaty of Nanjing.

Looking at the images Thomas LIN has created, I have conflicted feelings: quietness and intensity.

EV −3 16 is a picture of the bay in the moonlight. This picture reminds me of a time when the soil of this land didn’t know about human civilization yet, and the moonlight was the only ruler of the night. Looking back on human history, I think Hong Kong always looks like this. However, modern history did not leave Hong Kong alone. The city, which has developed independently as a British territory, has been transformed into a dazzling international city. The sight symbolized by EV −3 22 is the fruit of human insatiable desire.

And now the history of Hong Kong is rocking. Look at the portraits of young people taken with medium format camera, it is not the moonlight that makes them stand out, it is the light of the smartphone. In the fiercely blurred picture, I feel the will of young people is struggling, like living in a precarious future.

The flowing river never stops and yet the water never stays the same. Foam floats upon the pools, scattering, re-forming, never lingering long. So it is with man and all his dwelling places here on earth. (Hojoki / Visions of a Torn World by KAMONO Chomei)

It was written by KAMONO Chomei, a 12th-century Japanese writer. Countries and towns continue to flow like water, we drift throughout our history. However, it is the people living on this land who create this nonstop trend.

With news abounding about Hong Kong, EV −3 takes our eyes to a higher position. Think about the history of Hong Kong, a very unique city, and the moonlight that continues to shine on it.

The first image of the bay, this may not be a scene of the past, but a scene of the future.

HISHIDA Yusuke, Born in Tokyo in 1972, photographer / video director. He works document the manifestations of living history. His work ‘border’ was selected ‘Contemporary Japanese Photography’ of Tokyo Photographic Art Museum (2020). Books include: ‘2011-123’ (Sairyu-sya 2021), ‘border | korea’ (Libro Arte, 2017), ‘2011’ (vnc, 2014), ‘Aftermath – Photo after the Earthquake’ (with Kotaro Izawa, NTT Publishing2011) ‘BESLAN’ (Shinpusya, 2006), ‘One Day’ (Place M/Monday, 2006). Awards won include: ‘border | korea’ the (LibroArte) Photography Club Award (2018), Canon New Cosmos of Photography Exhibition (2008, 2010), Nikon Miki Jun Award (2006). His works are collected by Tokyo Photographic Art Museum, Seoul Museum of Art and Gimpo Cultural Foundation.

2019年7月1日

菱田雄介 2020

2019年7月1日是香港回歸的22週年紀念日,這城市處於高溫狀態。我在中環被大道上滿滿的人潮淹沒,我感到歷史正在變動。

到了烈日西下時,人流開始改變,他們紛紛停留在立法會附近。年輕人接連聚集,他們用護目鏡和面罩遮住了臉,還用保鮮紙包紮了手腳,這種情況意味催淚彈隨時會發射。

來自世界各地的攝影記者在俯瞰人群的行人天橋上排列,配備遠攝鏡頭的數碼單鏡相機都擠在一起,我注意到當中有一人出於某種原因在三腳架上裝有4×5大片幅相機,在那些不想錯過捕捉每一個瞬間的攝影師旁邊,他鎮定自若而沒有關上快門,那人是 練錦順。

熟悉相機的人都知道,大片幅相機通常不適合新聞攝影,底片必須每幅更換,並且需要較長的曝光時間,這會導致夜間拍攝時令影像模糊。當我感到疑惑的時候,這位神秘的攝影師開始跟我談論香港的歷史,那是一個關於月光和香港歷史的故事。

現在我看著當時拍攝的照片(EV −3 26),如果你仔細觀察這幅發白的圖像,您會注意到一條車道對角穿過畫面,一群人在它旁邊移動,畫出了一條像流水的軌跡,當中包含靜止的事物和變動的事物。我不禁想著那很久以前在這片土地上重複的歷史。

據說,練氏的作品《EV −3》是基於一個想像:1841年的香港人遇見2020年的香港時的樣子。1841是英國佔領香港島的那一年,翌年簽署的《南京條約》將香港永久割讓給了英國。

看著 練錦順 創造的影像,我感到靜謐和激烈兩種矛盾的感覺。

EV −3 16 是月光下的海灣照片,它使我想起了這處地方的土壤還不知道有人類文明的時代,一個只有月光才是夜之支配者的時代。回顧人類的歷史,我認為香港從來就是這樣子。但是,現代歷史並沒有拋下香港不顧,曾經作為英國領土而獨特發展的這座城市,如今已轉變成一個耀眼的國際都會,正如 EV −3 22 所呈現的光景,象徵著人類永不滿足的慾望之結晶。

然而現在,香港的歷史正在動搖。看看用中片幅相機拍攝的年輕人肖像,使它們脫穎而出的不是月光,而是智能電話屏幕的光芒。在劇烈模糊的畫面中,我感到年輕人們的意志在掙扎著,像生活在一個動盪不安的未來世界。

「川河逝水不絶,而此水已非原模樣;浮泡且消且結,哪有久佇不變之例。世上的人和棲所也不過如斯。」

這是12世紀日本散文家 鴨長明 的《方丈記》中的一句。我們生活的國家和城市就像水一樣流動,歷史長河永不停息;然而,一切流動皆是居於這土地上的人之所為。

當香港的新聞有如洪水之際,《EV −3》將我們的視線帶到了更高處,思考香港這個特殊城市的歷史,以及繼續照耀著它的月光。

一開始的那幅海灣照片,也許不是過去的場景,而是未來的場景。

菱田雄介,日本攝影師、導演,1972 年生於東京,以記錄生活和歷史的呈現為主題。2020年憑《border》入選東京都攝影博物館「日本新進作家」。書/寫真集包括《2011年123月》(彩流社 2021)、《border | korea》(LibroArte 2017)、《2011》(vnc 2014)、《アフターマス‧震災後の写真》(飯沢耕太郎合著 NTT 2011)、《BESLAN》(新風舎 2006)、《ある日、》(Place M/月曜社 2006)。獎項包括 2018年《border | korea》第30屆攝影協會獎、2008年及 2010年獲Canon寫真新世紀攝影展佳作,2006年Nikon三木淳鼓勵獎。攝影作品被東京都寫真美術館、韓國 Seoul Museum of Art、韓國金浦市文化財團收藏。

Disobedient Photobook

Wing Ki LEE, 2021

(extract from the article ‘Disobedient Photobook: Photobooks and the Protest Image in Contemporary Hong Kong’

Trans Asia Photography, volume 11, Issue 2: Asia, Fall 2021)

I would like to conclude this article by introducing Thomas LIN’s recent photobook 2020-1841 (2021). The book was started in 2017 as a personal project, when LIN became fascinated by Hong Kong’s historical photographs. LIN observes that the Umbrella Movement (2014) marked a beginning of Hongkongers deliberately making history photographically visible, or even photogenic. His project is not driven by a particular genre nor concept, but a desire to create a set of historic pictures of contemporary Hong Kong for the future. 2020-1841 reveals the ethos of disobedience in photography and photobooks of contemporary Hong Kong in two ways. Firstly, in the process of involving oneself in the protests and in photographing the protests, Hong Kong photographers resonated with the widespread yearning among Hongkongers to hold their faith and fate in their own hands. This has prompted photographers to explore and embrace a sense of self-determination and self-discovery in politics as well as in their exploration of the medium of photography. Hong Kong was conceived on the world map as a British colony in 1841, approximately the same moment when photography was invented in Europe. The earliest photographic images of Hong Kong were often made by Western photographers, for example John THOMPSON, Milton MILLER, and G. E. PETTER. The images were then exported to the West for foreigners to imagine the exotic Orient.* Hong Kong as a ‘foreign vision’ is now transformed to a local expression. The many photographers discussed in this article adopted innovative methods to challenge the traditions of journalistic, documentary, and humanist photography and to push the boundaries of photography in its materiality.

Secondly, the photographs in the boxset collection are digital C-type prints. A digital C-type print is made with both analogue (C for ‘chromogenic’ print as colour printing in the darkroom) and digital means (through a digital exposure system to project light in a C-type processor system). In the 1990s, Digital C-type print was a solution to address the limitations of the transition of analogue and digital workflows; however, the prevalent inkjet printing technology makes the digital C-type print a less popular choice among photographers. In East Asia, digital C-type printing is available in Taiwan and Japan only. This printing technique is neither widely available nor popular even though it is a good technology for photographic printing. The future of the digital C-type print is unknown and is perhaps soon to be dismissed. In a way, this printing technique offers an analogy for the political situation in Hong Kong. In 1984, DENG Xiaoping proposed a ‘one country two system’ policy, the famous principle to promise 50-years of prosperity (1997-2046) for Hong Kong’s transition from a British colony to a Chinese special administrative region. Like a digital C-type print, this was a solution to maintain a stable transition while taking advantage of two very different (political-economical) systems for a better future for Hong Kong. At a time when the new imposition is rapidly eliminating the ‘two systems’, LIN’s deliberate use of digital C-type printing today could be considered a ‘protest’ to the mainstream workflow as well as a subtle echoing of the general despair in Hong Kong when one extreme system is in the process of replacing an earlier, fragile equilibrium.

*Roberta WUE et al., eds., Picturing Hong Kong: Photography 1855-1910 (New York: Asia Society Galleries, 1997)

Wing Ki LEE is an artist-researcher based in Hong Kong. His research interests include photographic practices in the East-Asian context, post-photographic practice and critical digital humanities. His recent research project, titled ‘Disobedient Imageries: How new media, digital image technology, and algorithms redefine photographic truth in the public and virtual spheres of the 21st century?’ examines the roles and intersection of photographic imageries, civil disobedience, and technology. He is currently an Assistant Professor in photography at the Academy of Visual Arts, Hong Kong Baptist University and a visiting researcher at the Centre for the Study of the Networked Image, London South Bank University.